Bonjour les petits lapins!

Now that you are totally convinced that your supervisor is more going to influence your PhD success than the subject would, you are wondering how to identify a good supervisor. If I tell you “that’s the one that proposes good PhD subjects”, you’re going to throw me carrots, so I’d better develop a bit. I said “a bit”, but that’s a figure of speech. Difficult to develop it in just one paragraph and one cartoon.

It may seem ridiculously obvious, but I think a good research supervisor primarily needs to be a good researcher. First because I don’t believe it is possible to show well the ropes of any profession if you don’t master them yourself; second because it may be even harder to transmit the compulsory need for passion for doing research if you’re not good at it. And also, I am a strong believer that you learn much by seeing what you like and dislike in the way your supervisor does research even if it is not an explicit lesson. I believe in “leading by the example” even if I can resort to “do what I say, not what I do” when I mess up. So your supervisor should be someone you want to take example on. Better choose a good scientist then. Perhaps I’ll post one day on what I think this means. I don’t have enough enemies yet.

Should you choose a man or a woman? If you’re more confortable with either sex (but that’d be odd), then chose it. Otherwise, it’s an irrelevant question. Should you find a young scientist or an old one? Well, a young one is less experimented but probably has a smaller lab so more time and perhaps more enthusiasm, so there’s a balance here that means both can be good. One thing that is for sure is that he/she needs to like supervising, and to devote to you a significant amount of his/her time. That doesn’t mean just above 0.05, even if a precise percentage would be meaningless here. People have different ways of supervising, some leave more autonomy and are available upon request, some sit with the students in front of their computer to show them how to do stuff. Some spend a lot of time discussing ideas, or interpreting results. Regardless of the specific way, the importance is availability.

Your supervisor should not impose one immovable PhD subject but should instead build with you an excellent project that is tailored to you, that you will enjoy doing. That does not mean letting you work on dolphins or chimps because you’ve always loved them, but to show you what the lab does, understand what you seem to be most interested in and adapt the most topical subjects so that the subject will be gradually adapted to fit you while still being relevant to the lab and the most sexy, head-smashing brilliant subject ever. That subject will evolve with time during the three years of your PhD. Because science changes, because you will change, and because your first results will probably shift your initial priorities and interests. Your supervisor should encourage you to become gradually independent and to shape you thesis with his/her guidance. The subject has to become your baby, the one you work for, you wake up for, you fight for and are ready to die for. Ok, maybe I’m getting a bit ahead of myself but you get the idea.

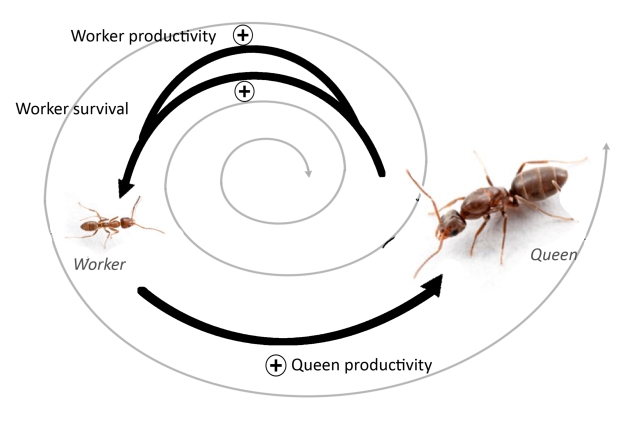

Over the course of your PhD, your supervisor must be prepared/able to show you, directly or indirectly, how to write research papers and grants, how to review papers for journals, how to prepare posters and talks, how to communicate to the public and how to prepare the next steps of your career. The two of you will form a team, so that’s one that has to be strong, to work on trust, and to aim for pride and success of the team mate. And it goes both ways.

Still there? Ok, you’re half way through the post, bear with me. So, how to you know who has at least some of these requisites? There are several ways. First, remember that the PhD interview goes both ways. It is also a way for you to assess whether the prof would suit you, seems to think the way you expect about a supervision, and if the lab more generally would suit you. I often say that students should be able to ask profs for recommendation letters from former students/postdocs, which they obviously can’t, but that’s a pity. Still, they can contact former students and lab members, ask around when they visit the lab and generally try to get info from students and staff alike, either upfront or more subtly according to the circumstance. Ask about the style of the supervision (not the quality, subtlety I said). Your supervisor should be proud of your work, let you present your data in meetings and mention your contribution when he/she presents it. Obviously, he/she should not put two or more students in competition over the same subject (and not have too many students anyway), write papers in your place, take ages to read and edit your drafts, fail to be encouraging or supporting of your limitations, deny you opportunities to take courses or to visit other labs to learn new methods/techniques. Your supervisor should not expect a given number of hours or day in the lab. If too much emphasis on this, then this is suspect. If your project is your baby, you’re not going to count the hours yourself, so why should someone else? Also, when you visit the lab (which should be proposed), try to assess the ambiance, if the students seem generally happy to be there (don’t confuse stress with discontentment). Finally, look also at the scientific output of former students, the number and quality of the papers they produce, as it’s likely to be indicative of your own once you’re there.

The perfect supervisor doesn’t exist, don’t look for that. But there are tons of very good ones over there, and I’ve given you some keys to find them. But most importantly I think, I’ve told you that it’s more important to make your choice over the supervisor than over the topic. Ah, and one last thing that I think is essential. You should like your supervisor, or at least not dislike him/her upfront. Whether or not to bond with students/supervisor is a very interesting topic per se – one that I’ll treat later – but just… no, I said later.

Now, I’m of course not trying to imply that I’m all that. Supervising is not easy and even if you know what you’re supposed to do on paper, managing to do it on a daily basis is not that obvious. Plus, a supervision is a two-ways relationship and it cannot work well if the student is not fully in the game. And believe me, finding a good PhD student is at least as hard to find as a good PhD supervisor. Ah! Just to end up on a nice note: I’ve been very lucky with all my PhD students so far, and totally blessed with the last two.

So, obviously, next post: how to fool your potential supervisor into believing that you would be a good PhD student. Or my own personal expectations during student interviews.